Cornwall's dispute with England

After 500 years the Cornish plan to commemorate the march to London by their disgruntled ancestors who complained about the taxes imposed upon them.

In 1497 Cornwall was a distant part of the kingdom more easily accessible by ship than overland. The few people who visited Cornwall would have found a motley mess of small, impoverished towns, villages and hamlets. Its people lived frugal lives scratching a lawless living by farming, fishing, mining and stealing whatsoever they were unable to obtain by fair means.

The arrival of Henry VII on the throne did not unite the kingdom. Social order was collapsing and plotting and intrigue were rife at court. Perkin Warbeck, who pretended to be one of the princes reputed to have been murdered in the Tower of London, claimed the throne.

The Scots were a particular threat and supported the Pretender. When news reached London that King James IV of Scotland had crossed the border into northern England accompanied by Warbeck and an army Henry's government prepared for full-scale war.

A new tax was levied to raise an army to fight the Scots. Commissioners were appointed to collect the tax. They, in turn appointed local collectors. In Cornwall the Provost of the powerful Glasney College in Penryn, Sir John Oby was appointed and commenced his task with zeal. The people of Cornwall had no money for taxes and hated this ecclesiastical man and his well known methods of seizing common grazing land.

The people of The Lizard peninsula were the first to rebel. They found a leader. A man of fairness, great strength and courage, Michael Joseph the smith (an gov) at St. Keverne. As anger spread through Cornwall leaders were found in each district. In Bodmin the people found their intellectual leadership in Thomas Flamank, son of estate owner Sir Richard Flamank In his twenties, he was an eloquent lawyer in the King s court. We don't know why he was moved to lead a bunch of common rebels but can only suppose he was opposed to the clear unfairness of the taxation.

Flamank spoke out against the tax, that it was not necessary to tax the Cornish people and that the troubles in the north were the concern of nobles who benefited from their protection of the kingdom. Disquiet grew and in May 1497 an army of some 3,000 left Bodmin for London. Flamank had persuaded the Cornishmen that they marched in peace to carry their grievances to the king. They had only bows and arrows and simple country tools.

They marched without violence receiving support along the way. Their numbers increased daily and so did their fervour. In Somerset their numbers swelled to over 5,000 and included James Touchet, Lord Audley. They clearly intended to fight for what they saw as justice. They approached London from the south expecting the support of the Men of Kent but this was not forthcoming.

Henry summoned his military adviser, Lord Daubeney, who had assembled an army of 8,000 soldiers in London in preparation for the war against Scotland. This was unfortunate for the Cornish. Revolts by large groups of commoners were virtually unknown. The city gates were closed in the face of an army which was now reported to be 15,000 strong, although it was probably not half that size.

Daubeney formed up on St. Giles Field to protect London. A message was sent to him seeking a general pardon and offering to hand over the Cornish leaders. Daubeney did not accept, wishing to show his military ability. The Cornishmen reached Blackheath on the 16th June where they could look down on London.

They now saw that Henry's army was greater than anything they had ever known and during the night many are reported to have slipped away. Official reports speak of nine or ten thousand being left by the morning. Again this is probably twice the real number.

The rebel Cornish placed a single rank of archers near the river bridge at Deptford Strand. Michael Joseph and his army were encamped at the top of the hill. The King divided his army into three units. One to attack the hill from the front, one from the rear and the third in reserve. With the hill surrounded Daubeney's spear-men broke the rank of Cornish archers who, with no second rank for support could offer little resistance. Daubeney then charged and captured the heath. Two hundred Cornishmen died compared with just eight of the King's soldiers.

The King was delighted and gave thanks to God for deliverance from the rebellious Cornishmen. Michael Joseph joined Flamank and Audley in the Tower and a week later they were tried and condemned. Joseph and Flamank enjoyed the king's mercy by being hanged until they were dead before being disembowelled and quartered. Audley's sentence was commuted to beheading.

On the morning of the execution Michael Joseph was dragged with Flamank from the Tower to Tyburn and declared that he would have "a name perpetual and fame permanent and immortal". The heads of the three men were set on posts on London Bridge.

This ended the bloodshed. The exhausted and beaten Cornish now had to pay fines as well as the taxes. The survivors trudged home to Cornwall, broken but with pride for the martyrdom of their leaders. The taxes on the Cornishmen and the treatment dealt by the King were not forgotten.

In 1997, a commemorative march named Keskerdh Kernow (Cornish: Cornwall marches on!) retraced the original route of the Cornish from St. Keverne to Blackheath, London, to celebrate the Quincentennial (500th anniversary) of the Cornish Rebellion. A statue depicting the Cornish leaders, "Michael An Gof" and Thomas Flamank was unveiled at An Gof's village of St. Keverne and a commemorative plaque was also unveiled on Blackheath Common.

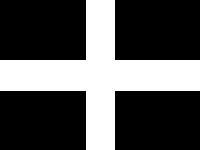

Cornish Stannary (Tin) Law Cornwall's History Mining in Cornwall